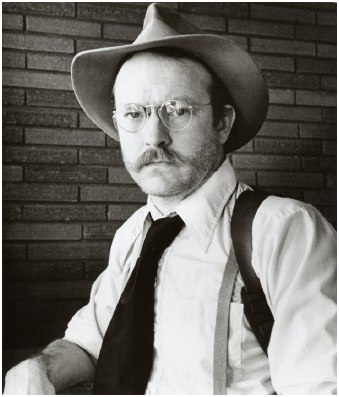

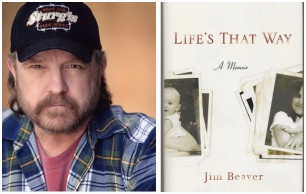

Jim Beaver is known for his character acting on TV, in motion pictures, and in the theater. Jim is also a writer who has been working on a book about George Reeves for many years. His recent book, Life’s That Way is a memoir about the death of his beloved wfe, Cecily. (Life’s That Way was published by Putnam and is available at Barnes & Noble; to learn more, click here.) Life’s That Way is filled with gentle humor, honesty and gripping compassion. Jim Beaver is a busy man; juggling between his personal and professional schedules, it took almost a year to complete this interview.

Life Jim Beaver’s Way

Interview by Susan Schnitzer

(This Interview was first published at the George Reeves Forever website on June 1, 2011.)

Career and Life

SS: What was your name at birth?

JB: I was born James Norman Beaver, Jr. I was named after my dad, who was named after the doctor who delivered him.

SS: What is your ancestry?

JB: Cherokee and German on my mom's side, English and (very far back) French on my dad's.

SS: What in your background made you decide on your path in the entertainment field?

JB: I was a movie buff since childhood and I wanted to be a film historian/biographer. But I couldn't find an academic situation that fed that goal directly, so I tried theatre as a major, as a substitute related field. That's when I decided to be an actor and playwright.

SS: Which do you consider yourself to be predominantly, an actor or writer?

JB: I'm an actor through and through. I've written a lot: books, articles, plays, movies, TV episodes, but I consider myself first and foremost an actor.

SS: What kind of plays did you write/act in while in college?

JB: I only wrote 2 or 3 short plays in college: an adaptation of O. Henry's "The Cop and the Anthem," a Shakespearean spoof called "As You Like It or Anything You Want To, Also Known as Rotterdam and Parmesan Are Dead," and a one-act about an old derelict who claims to be Clark Kent. That play later became a full-length work and was my first play to be professionally optioned.

SS: What venue do you prefer: westerns, Shakespeare, sci-fi, etc.?

JB: As a performer? I love most genres. I'm nuts about Shakespeare. I've done a lot of it, but not in a long time. Nothing is more fun than doing a Western. I'm not a science fiction fan, but it’s good work if you can get it. I'm more interested in good characters and good writing than in what the genre is.

SS: You had various occupations before becoming an actor; did you draw on these experiences for your characters?

JB: Well, sure. Everything an actor does is drawn from his own experience. I'm not sure I could point to any particular occupation and say, oh, yeah, that fed this role or that one. Of course, there aren't many chances to play a Frito dough mixer or pre-school bus driver or a drive-in movie projectionist, so direct connections are kind of rare. But I draw a lot on how certain jobs felt, how the people I worked with were, that sort of thing.

SS: In the HBO series "Deadwood": How did you get the part? What timeframe is it set in?

JB: I auditioned for "Deadwood" just like most of the other actors. I had worked for producer David Milch once before, on "NYPD Blue," and I'd worked for director Walter Hill in "Geronimo," so they kind of knew me. But it was the audition that got me the part, not the previous work. "Deadwood" is set in Deadwood, Dakota Territory, in 1876-1877.

SS: Your character’s name is … Whitney Ellsworth, the prospector! Apparently this character’s name is an inside joke on the producer and story editor on TAOS. Was this your idea for the character?

JB: The first season, my character didn't have a first name. He was just known as Ellsworth. But in the second season, it became necessary to provide him with a first name, for story purposes. The writers gave him a first name, but I asked producer David Milch if we could change his name to Whitney Ellsworth in honor of "a friend of mine." The real Whitney Ellsworth was not a friend of mine -- I never met him -- but I was extremely happy when my request was granted.

SS: Are there any similarities in the persona of the original Whitney and this character?

JB: My guess is that the only similarities between "Deadwood"'s Whitney Ellsworth and "Superman"'s is the basic human decency of each. My character was described to me as "the conscience of the town," and beneath his gruff exterior he was a very noble and decent man. Everything I've heard about the real Whit Ellsworth suggests that he, too, fit that description.

SS: How do you prepare yourself for the shift in characters i.e. Bobby Singer (Supernatural) and Sheriff Charlie Mills (Harper’s Island)?

JB: I guess I just read the scripts and play what's on the page! Every actor has his own process. Mine doesn't involve a lot of thought about shifting into character. Rather, I read what's given to me and my instincts tell me how to play it. Then the director tells me how *really* to play it!

SS: Are all of your characters gruff but kind hearted?

JB: Not at all. I've played cold-blooded hit men, child molesters, very timid and sweet characters -- a wide, wide range of parts. But I'm probably best known for gruff but kind-hearted roles.

SS: What future projects are you going to take on?

JB: I'm going to start filming the seventh season of "Supernatural" soon. I don't have anything else scheduled, but that show takes up most of my time, so I don't get to do much else, except the occasional guest-starring part on another show.

SS: What do you consider to be your main accomplishment in the arts?

JB: My main accomplishment in the arts? Making a living in them! For every job, there are a hundred thousand people trying fairly actively to get it, and fewer than 1/2 of 1% make a living acting, so to be able to do so is a major accomplishment, one I ascribe to equal parts preparation, hard work, and amazing luck. Talent may have something to do with it along the line somewhere, but it's meaningless without those other factors. In a broader sense, I feel a great sense of accomplishment whenever something I've done as an actor or writer has moved people, or informed them, or relieved them of the day's burden, or caused them to shed a prejudice or to forgive a slight, or, at least, to consider such things. I have great fun doing what I do, but I do what I do because I'm able in a small way to touch people in a positive way -- even if it's only by showing them what to avoid. The closest I ever come to feeling even a tiny bit noble is when my work goes before an audience. I'm very grateful for the chance to do what I do.

George Reeves

SS: What drew you to TAOS and George Reeves as Superman?

JB: I was drawn to TAOS and George Reeves the same way most baby-boomers were: I fell in love with the show as a kid. Eventually, my attraction to Reeves was greater than my attraction to the show. I was consumed by curiosity about him, both his life and his death, as well as the other roles he played.

SS: Did George Reeves inspire you to become an actor?" If so, how?

JB: I don't know that George inspired me directly to become an actor. It's hard to think of any actor whom I looked at and said, "Oh, I want to be like him" as far as performing goes. Probably the closest thing to an inspiration I had was John Wayne, but even there, it was more about being like him as a person than being like him as an actor. However, I learned a great deal about being an actor from George Reeves -- not so much from his performances but from what I learned about the life of an actor during my research into his career. I daresay I've avoided some real pitfalls due to my knowledge of some of George's career difficulties.

SS: Many people are vehemently opposed to the official police verdict that George Reeves committed suicide. Instead, they believe that George Reeves was either murdered or accidentally shot. What do you think?

JB: I don't want to go too heavily into this, primarily because I want to save the details of my conclusions for my book, but also because no matter which side one lands on, it tends to make some people angry. I've been far too outspoken about my thoughts over the years, and I should not have given so many opinions out loud without the backup of the years and volumes of research that have gone into my work. I will just say that I at first, as I was just starting my research, believed that George had been murdered, but that hundreds of interviews with people directly involved with the events, as well as my own wide-ranging study in criminal forensics and medical pathology have led me to a different conclusion. I feel pretty firm in this conclusion,

but I feel even firmer in the conclusion that the real truth will never be known beyond all doubt.

SS: Do you still have plans to publish a biography of George Reeves?

JB: I absolutely still plan to publish my book on George. It is both my enormous good fortune and my great sorrow that my acting career has been so busy and so successful that I cannot devote the same amount of time to the book as I want or as I used to. Being a widower with a little child has had an enormous impact on my ability to commit time to the project as well. But I work on it whenever I get a break, and as far as I'm concerned, nothing but death will stop me from getting it done and published.

SS: Any idea when that might happen?

JB: I gave up guessing when the book would come out a long time ago. I should have given up guessing when a lot longer ago than that, as I on several occasions made predictions or promises that turned out to be wildly inaccurate. At one point, I thought I had it just about done and ready to publish, but a vast array of new information came into my possession at about the same time that my wife was dying, and it became both premature and impossible to live up to that prediction. You don't know how badly I feel about the years it has taken, yet at the same time, those years have provided new material that would have gone undiscovered if I'd published back when I first thought I would. So the Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away, and vice versa!

SS: With the enormous amount of research into the life of George Reeves, are there any amusing anecdotes or little-known facts which you would be willing to share?"

JB: I'm sure this will bother some folks, but I think I've spilled too much in recent years already! I'd love to titillate your readers with some new stuff, but I think I'm going to fall back on that old cliché, "Wait for the book!"

SS: What impact do you think your consulting on Hollywoodland had on the movie?

JB: My experience consulting on Hollywoodland was much different than I expected it to be. I've been working in Hollywood for three decades now, and I'm very familiar with how quickly movie executives are ready to dump all pretense of accuracy and honesty in order to provide what they think will excite or thrill or shock an audience, even if it's not true. In fact, I had turned down a very large sum of money for the rights to my book-in-progress about five years before Hollywoodland because the people who wanted those rights made it very clear that they didn't care about George's life or what really happened to him, but just wanted a sexy murder mystery. Their description of what they had in mind turned my stomach and I told them that if they wanted to tell that story, they would have to do it without the rights to what I was writing.

Over these many years, I've come to love George Reeves as a person, almost as if I'd known him in real life. I *do* know him better than many people *in* my real life, and I'm very protective of his persona. What that studio had in mind would have boggled the minds of George's fans, and it was a very easy decision to turn them down. (I wish they'd given me the money anyway, 'cause it was a bundle, but people rarely give you money after you've told them what they can do with it!) So when I was approached by the Hollywoodland people, I expected the same situation. But it turned out to be quite different. Unfortunately, I wasn't approached until very late in the pre-production process, when a great many things were already in place that couldn't be changed. But director Allen Coulter made it very clear that he desperately wanted to do right by this story and that he would change anything I asked if it were possible to do so. The earliest draft of the script I was given had a huge number of problems from my perspective, a ton of nit-picky stuff but also far too many major errors and misinterpretations. I turned in pages and pages of notes, pointing out minor errors such as the notion that George and Rita Hayworth would not have known each other (as an early scene suggests) when in reality they'd played lovers only a few years earlier. I also pointed out what I thought were huge inaccuracies, such as the suggestion that George's mother could be bought off the investigation. As we all know, she never gave up her own belief that he was murdered and the picture's suggestion that she backed off is a real sore point for me. But the director and producers were always interested in what I had to say, and they made numerous changes at my suggestion.

They also consulted me on casting, and I'm happy to say that if it weren't for me, Harvey Keitel would probably have played Eddie Mannix, rather than Bob Hoskins, who in my opinion was so much like the real Eddie it was frightening. I provided pictures of the real characters so that casting could make the best choices possible (Lois Smith as Mrs. Bessolo is another one I thought was perfect casting). But as I say, the pre-production was almost complete when I came aboard. Unfortunately, something that most people outside the film industry don't realize is that there is a budget for scripts, and when that budget is exhausted, a studio will virtually never authorize further re-writes. That was the case with Hollywoodland. The last draft, by the uncredited Howard Korder, was a gargantuan improvement over the previous script I'd seen, with much of George's decent, open personality restored and with a lot of the errors fixed. But that draft also exhausted the script budget and because no one can alter the script after the studio pulls the plug on the script budget, there were a good number of further changes that couldn't be made. The director made certain to tell me that if they'd brought me aboard much earlier in the project, they'd have incorporated many, many more of the changes I asked for. As it was, he managed to incorporate a few more of them in the editing, merely by cutting out things I'd objected to.

In my whole history working in movies, I've never met a director more dedicated to getting it right and more disappointed that he couldn't get it all right. Most of the time you hear the dreaded phrase, "No one will notice." That's the opposite of what I heard during the work on Hollywoodland. What I heard most of all was "So, okay, what really happened?" or "Is this accurate?" We had a bit of a go-'round about the kid-with-the-gun scene, but that was one of those things that was too late to change and, as one of the more dramatically powerful moments in the script, it couldn't just be cut out or the dramatic arc would have sagged with nothing to hold it up there. And when one considers that George himself apparently made up the story that scene was based on, it's hard to give him dramatic license and not give it to the filmmakers, too! All in all, my experience on Hollywoodland was extremely positive, I was listened to and paid attention to, and whenever possible within the very tricky business of getting a movie made, the changes I asked for were generally honored. (One thing I liked was how much the filmmakers *hated* Hollywood Kryptonite. Apparently the studio forced them to give credit to the book, but everyone I talked to seemed to agree with Jack Larson about "Hollywood Kraptonite." Jack, by the way, loved the movie. But Jack's a producer of many years' experience, and he knows how difficult it is to get everything perfect, even when you want to.)

SS: Are you happy with the way the movie turned out?

JB: I thought it was about the best George Reeves movie anyone would ever get a Hollywood studio to release. I wasn't 100% satisfied, for the reasons I mention, but after all my years in the business, I'm astonished that a movie ever got made that was anywhere near this accurate. It's far better than what could have happened. And I liked Affleck, Lane, Hoskins, and Smith a great deal.

SS: How would you rate George Reeves as an actor?

JB: I think George was a good journeyman actor. He was no Olivier or Robert Duvall (who is?), but he almost always acquitted himself well and sometimes nobly. I've seen a couple of performances of his that are weaker than others, but for the most part, I always enjoy watching him. Interestingly, as much disdain as he may have gotten (or felt) for the Superman show, it may be his best dramatic work, as he is far more at ease in the character than most actors would be. He seems to be utterly unself-conscious in the part, and that's a key secret to good acting. I love him in "So Proudly We Hail!" and any number of other roles, but sometimes I think his greatest performance may have been on "I Love Lucy." He's so completely natural, so joyous in the performance, so confident and bright in his demeanor. I just love watching him in that appearance.

SS: Do you think that he could have made it big as a movie star if Mark Sandrich hadn't passed away?

JB: I know George blamed his career difficulties in part on Sandrich's passing, and it's possible that Sandrich would have championed him into better and better roles. But there are aspects of this that aren't as evident without digging beneath the surface. "So Proudly We Hail!" was an extreme rarity for Sandrich -- a drama. Almost everything he did in the forties was either musical or a Jack Benny comedy. His entire career was branded pretty much by musicals with Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, and it's hard to imagine where George would have fit into that kind of film other than as the "other" man or some other less-than-stellar supporting role. (Does anyone even remember who played the "other" man in all those musicals?) The other thing to consider is that George's heyday (and Sandrich's) was during the Golden Age of the studio system. Unlike today, when a movie director's casting choice is usually the final word, in those days the director was a hired gun and most casting decisions were made by the studio, not the director. George was under contract to Paramount, yet even when he returned from the war, they didn't do much with him, and it's hard to believe that Sandrich, as a contract director, would have been able to make them cast him if they hadn't thought to do so themselves. Nowadays, of course, becoming a favorite of a big-time director can mean a beautiful career, but in those days, it was much better to be on the studio's list of favorites than on a director's. The truth is that it was the war and not Sandrich's death that stopped George's career. Disappearing for nearly three years cost dozens of actors their careers, and George was just one of many. Not that it might have mattered. The biggest parts George was scheduled for at the time he went into the army ended up going to Dennis O'Keefe. Not exactly Robert Mitchum, eh? O'Keefe didn't go to war, and his subsequent career was only marginally better than George's. So I don't think it's helpful to blame it all on one thing or another. If I had to pick one major cause, it would be the war.

SS: What were George’s vices?

JB: Define vices! Well, he smoked for years, and he drank enough to surprise most of his friends at his capacity. According to a couple of my sources, he liked to smoke a little pot and he certainly liked his romantic activities. There are some other things that some might call vices, some might not. When the book comes out, everyone can call them what they want!

SS: Did George’s vices stand in the way of his career and his life?

JB: I don't think so. Yes, we've all heard the stories about him needing to get the stunt scenes done before his liquid lunch, but it's hard to think of that as having an effect on his career, because no one on TAOS seems to have minded much and he didn't have much of a career at that time, aside from TAOS. I've never heard of him having job difficulty because of his drinking. His drinking was indeed excessive, but I've never heard a negative word about him and his work related to drinking. In fact, I've heard quite the opposite that he managed always to do what was required of him (except maybe for after-lunch stunts on TAOS!), no matter how much he'd had to drink. What other vices he had, I don't have a sense of a negative impact on his career. Of course, as I say, define vices. George seems to me to have been a fellow with very few of what modern-day folk would call vices.

SS: What were George's religious beliefs and practices and how did they differ from Toni's?

JB: George was raised, sort of, in what was then known as the German Reformed Church, and indeed his great-grandfather was a pillar of that church. But his mother doesn't seem to have adhered tightly to that or any other church, at least until late in her life, and I haven't run across any information about religious practices throughout most of George's life. Once he became involved with Toni Mannix, a devout-ish Catholic, he attended church with her, but I've seen no evidence that he ever actually joined the Catholic church. (I attended Catholic services for years with my late wife, but I never professed to be a Catholic or practiced Catholicism. I suspect that George's experience was similar.)

SS: Have you encountered anyone who disliked George?

JB: One of the most pleasant things about this entire project, lasting some thirty years now and covering hundreds, if not thousands of interviews, is that I've not met anyone who had anything bad to say about George or professed to dislike him. The only half-way unpleasant thing anyone told me about him was from a girlfriend he'd broken up with prior to his marriage to Ellanora, and even she talked very kindly about him until a couple of hours in when she'd had a little too much to drink. ("Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned!"). That's a pretty good record, and quite indicative, I think, of what a terrific fellow he must have been.

SS: Why did George get divorced?

JB: That's a very complicated story, and there's a good deal of responsibility on both sides of that marriage. The basic foundation of the divorce was that the couple had grown very far apart during their wartime separations and by the late forties were seriously incompatible. Other elements were at play, but they're too complex to deal with here.

SS: Did he really want to have children?

JB: It depends on whom you talk to. I've heard some people say yes, very much, while others say "Not on your life!" That's one of those questions that will have to be answered by each individual by means of personal interpretation. I can't give a solid yes or no.

SS: Did George have an affinity for guns?

JB: Absolutely. George loved guns and had several that he owned. He doesn't seem to have been much of a hunter or sportsman, but he certainly owned quite a few weapons. Unfortunately, George was widely known among his friends for his carelessness with guns and for foolishly playing with them when intoxicated. Several different people have told me of very dangerous "games" George would play with guns while drinking, dating back to the 1930s.

SS: If so, why?

JB: I have no idea why anyone has an affinity for guns. I suppose such an affinity is different for every individual. George doesn't seem to have talked to anyone about why he liked guns, and I've not encountered anyone who ventured an opinion.

SS: Should there be a George Reeves museum somewhere?

JB: Well, of course, I think so! I'm a fan. Whether there's a market or a clientele for such a museum is hard to say. We baby-boomers are dwindling, and I'm not sure there are enough of us around to make a going concern of such a thing. After all, Rudolph Valentino was the biggest star in the world in 1925, but do you think a Valentino museum could stay in business these days? A few more years will *be* "these days" for our George. But do I think he deserves the honor? Absolutely!

SS: What do you think of the plans for the new Superman play?

JB: You mean a stage play? First I've heard of it.

SS: How about Lois Lane, Superman's biological father, and Perry White being black?

JB: First I've heard of it.

SS: How about the plans to make Superman more like the Superman of the 1950s?

JB: First I've heard of it. (Sound like a broken record, don't I?)

SS: What did you think of the movie "Superman Returns",( e.g., Superman's pre-marital affair with Lois that resulted in a love child)?

JB: I didn't care for that aspect of the movie very much. I'm a traditionalist, and I'm very much stuck in the earlier incarnations of Superman. That didn't fit in with my sense of the legend. But as I described in my comments about Hollywoodland, most of the time the studio execs don't care much if they stray from the facts or the legend, as long as they think it will sell tickets.

SS: Did this tarnish his wholesome, American Way image?

JB: Not particularly. I just didn't think it was necessary. Of course, when you realize that the U.S. is 7th in the world in unmarried pregnancies, with 40% of all U.S. babies (as of 2007) born out of wedlock, it's hard to argue that it's un-American! But that's not why I go to a Superman movie. That's soap-opera stuff, and I don't need it.

SS: Are you looking forward to Chuck Harter's book on how George died?

JB: Yes. I'm interested in everything that's published about George, and I'm particularly interested in Chuck's take. He and I have had lots of long talks on the subject and we agree on quite a bit, with still plenty of room for alternate ideas.

SS: Who was the originator on your theories about George (you or Chuck)?

JB: My theories are entirely my own. I think Chuck has come on his own to agree with some (not all) of them. But my conclusions were pretty much established back before Chuck agreed with me on any major aspect. I've been in Canada and Europe much of the past couple of years, and haven't had a chance to hang out with Chuck in far too long. But when we last spoke, we seemed to agree on a great deal more than we had in previous years.

SS: When and why did you decide to write about George Reeves?

JB: I was interested in George's life from my teen years and may well have thought about writing about him by the time I got out of the Marines. But my first clear memory of an active decision came in 1978 when I was writing for the National Board of Review's magazine "Films in Review." I was asked to do an article on George and I jumped at the chance. Subsequently I realized that there was far too much intriguing and interesting material for a mere article and I set out on the path toward a book, a path that turned out to be far, far longer than I ever dreamed. It's good I didn't realize how long I'd be working on it, as I'm sure I'd never have started it if I'd known. But one great thing about starting so long ago is that I was able to interview scores of people who are now long gone. People like James Cagney, for example.

SS: What do you hope to uncover about George?

JB: The truth. That's all I care about. Good, bad, interesting, dull, all of it. I want to know and tell the truth. If I don't *know* the truth about something, I want to present as much evidence as possible so that my readers can decide what is most likely the truth. But I don't plan to say something is the truth if I don't know for certain it is.

SS: Will these discoveries “shock” the reading audience?

JB: It depends. Some people are shocked by things other people take in stride. I can't predict what any particular person will experience. I know that, compared to the lives of many famous people, particularly film and TV stars, there's nothing very shocking to be revealed about George's life. The worst thing I can think of him ever doing is driving drunk, and that's hardly a shock to anyone who knows about George's life. Anyone expecting to find out that he was a Soviet spy or ate babies for breakfast is going to be shocked, I guess, and sadly disappointed. Frankly, a few more seriously shocking things would probably mean better book sales, but I'm not going to create shock just to have it. Okay, here's a shocker: If the moon were made of Swiss cheese instead of green cheese, it still wouldn't have as many holes in it as Hollywood Kryptonite does. Yeah, I know. Shocking!

SS: Fans have been wondering for years about when your book will be available, and you've often explained how family and career matters have played havoc with self-imposed deadlines. How much work remains in the form of interviews to be transcribed, historical articles to be culled for excerpts and actual writing?

JB: With the new material relatively recently uncovered, it's more difficult to say, but primarily what's left is a still-massive job of transcribing and much of the actual writing. But the actual writing is the fast part. In all my other experiences, the research and transcriptions have taken twenty times as long as the actual writing.

SS: And, if you had no other obligations, how much time would it take to do it all?"

JB: See above. It's impossible to predict, and I've made a fool of myself too many times trying to predict. Heaven's my witness; I wish I had a better answer.

Life’s That Way

SS: What has been the reception to your recent book, Life's That Way?

JB: The response to Life's That Way has been a thousand times greater than I expected. It seems to have touched more people than I could ever have dreamed, and I am overwhelmed with letters and messages from people who've read it and found something meaningful or useful to them. My gratitude is beyond measure.

SS: Why did you pick Barnes & Noble to publish the book?

JB: Well, actually Barnes & Noble is a bookstore chain, not a publisher. Life's That Way was published in hardback by Putnam/Penguin Books and in paperback by Berkely Books. (It's also available in Chinese and Italian editions.) Barnes & Noble chose it as one of their annual Discover Great New Writers winners, but they didn't publish the book themselves.

SS: How did you get the title of your book?

JB: I'd prefer not to give away the story of how the title phrase came about, because it's a vital part of the experience of reading the book. What I will say is that the title refers to a direction, not a quality.

SS: Did writing the book in email form make it easier to write the memoirs?

JB: Yes, in that the emails *are* the book (though greatly edited down). I wrote of that year’s experience every night, as events were occurring, and there was something important about doing it that way, rather than writing in the aftermath of events. I don't think I could have written the book after the fact.

SS: Did your exchange of emails from your friends help you to cope better with your wife’s illness?

SS: How did it help?

JB: It allowed me to put my feelings into thought and thus to be able to manage them and understand them and as a

result, to cope with them.

I'm not sure I could have survived that year if it weren't for the sharing my nightly emails allowed me. I don't know how anyone survives fear and loss of that magnitude, keeping it all inside.

SS: Did being an actor help you to cope?

JB: It did help, in several ways. For one thing, it gave me something to do to take my mind somewhat off what was happening in my personal life. It allowed me, too, to be in the fellowship of my colleagues. There are few more generous, decent people than actors, I've found, and they held me up many times when I thought I must collapse. Additionally, after the loss of my wife, I was blessed to be able to use the experience in certain parts of my acting. Twice I was assigned to play someone who had lost a beloved wife, and I was blessed not to have to imagine what that was like, but to be able to go instantly into a much more authentic place than other actors would be able to go. I'd rather have not had the knowledge, of course, but having it, I felt enormously grateful for the chance to do something positive with it.

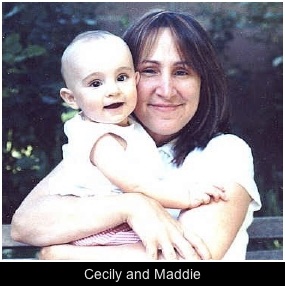

SS: Did your marriage and relationship with your wife grow because of her illness?

JB: Oh, yes. Like all marriages, we'd had bumpy spots, and not even dire illness changes that, but we grew so closely aligned, so simpatico in the four months we were allowed after Cecily's cancer was discovered. We had always been close, but nothing brings you together more tightly than the possibility of losing each other forever.

SS: Did your relationships with family and friends grow because of her illness?

SS: Do you still keep in contact with your email friends?

JB: Yes, I made scores of friends or deepened relationships during that time, and I still am very close to many of those people, great numbers of whom I didn't know or barely knew before that time.

SS: Which friends helped you the most during Cec’s illness?

JB: It's too hard to count the hundreds and hundreds of gestures of goodwill and help we received, and impossible to list all the most helpful. A few people well-known to TAOS fans were of inestimable support and helped bear up me and my family during that time: Stephanie Shayne, Michael Hayde, and Jim Nolt.

SS: What have you learned from Cec’s illness?

JB: Well, it took me a whole book to describe what I learned from Cec's illness and death, so I can't encapsulate it all here. But foremost, I learned that good people are everywhere, that all of us have our tragedies but few of us learn the blessings of opening up about them, that forgiveness is not condoning bad behavior but rather refusing to continue feeling bad because of a slight, and that whatever you think or expect the future to hold, the real experience will be different. Most importantly, I learned that life's that way.

SS: Do you now donate some of your time to lung cancer research and sufferers (support groups)?

JB: Because of the popularity of the character I play on "Supernatural," I am frequently given the opportunity to direct charitable giving to an organization of my choice, and the show's fans have been marvelous about raising money. I support the John Wayne Cancer Foundation (www.jwcf.org) and whenever I'm asked to recommend a charity, that's the one I name.

SS: Did you receive any family flack over the morphine drip that was given to Cec during her illness?

JB: I'm not sure what you mean. Cec received morphine at various times during her illness, but if you're referring to using morphine to help her die more easily, that did not happen. We fought for her survival up until the last hours when it became clear that it was impossible for her to survive. She was already unconscious at that point and had been for several days, but it was not due to a morphine drip, nor was one initiated at that time.

SS: Do you think that the morphine helped her or hindered her in any way?

JB: The only time she had morphine was on occasion when the pain in her bones grew severe. She didn't like it and wanted to be awake and aware as much as possible. But as I say, morphine was never used to ease her dying. It was used at times to ease her living. And morphine had nothing whatsoever to do with her death, which came about as a direct result of her lungs becoming unable to absorb oxygen due to the damage caused by cancer cells.

SS: Since Cec suffered with a bad back for many years, do doctor’s speculate that she may have had undetected lung cancer for many years?

JB: There was speculation that Cec may have had cancer for up to a year before it was found, but not "many" years. We were told that the particular kind of cancer she had is almost never caught early, and indeed, it was only found when it was because it had spread to her bones. By the time it was found, there was really no hope, other than miracles.

SS: What was your relationship like with Don Adams?

JB: Don Adams was my father-in-law, and he was a fascinating character. He was a difficult, prickly man, only peripherally interested in anyone except himself, but I liked him to the extent he allowed anyone to like him. He was amazingly funny, and was one of the best story-tellers I've ever heard. We got along very well (especially considering that Cecily predicted when we started dating that he would hate me!). We shared a love for old movies and the Civil War, and while it was almost impossible to have an intimate conversation with him, we never lacked for material to discuss, because we could always talk old movies. He was quite hard on his children, and could be selfish and mean beyond what I was used to in any of my other relationships. But I think he loved his family as well as he could. He just didn't have it in him to be very loving. We also shared being former Marines, and I think he liked me for that. He was always conscious of how close he came to dying on Guadalcanal, and I think it colored his whole life afterwards. Very interesting man. As I say, I liked him to the very limit that he would allow.

SS: Do you ever feel Cec’s presence to this day?

JB: I don't know that I necessarily feel Cec's presence, but I find myself talking to her often. I don't know if she hears, but it doesn't keep me from talking to her.

SS: Does your daughter?

JB: My daughter's memories of her mom are mainly reflected ones. Maddie was only 2 1/2 when Cec died, so she remembers only pictures and videos and stories I tell her. I don't think she has much emotional sense of her mom's presence, but she very much insists that Cec can still hear and see us.

SS: How do you keep Cec’s memory alive for Maddie?

JB: I keep Cecily's memory alive as well as I can by talking openly about her, by keeping Cec's pictures visible all around the house, by telling Maddie about similarities and differences between them, by visiting the redwood tree in a nearby park where Cec's ashes are in part scattered. We are always very open about her mom and about our loss and about our history. I hate with all my heart that Maddie doesn't actively remember Cec, but I do everything in my power to keep her mom alive in her heart.

SS: What is your message to your readers about Cec’s illness?

JB: It's really encapsulated in what I said before about what I learned through the process of writing about those events. Life isn't something that happens, it's something we move toward, and we must always keep moving toward it. I can tell you that she never once let up in doing so.

SS: Did the illness make you a better person?

JB: Cec's illness made me a man, if nothing had done so before. I feel useful in this world now. I'm not sure I did before.

Summary

I want to express my sincerest thanks to Jim Beaver for giving me this opportunity to interview him. I thank Jim for the 4 hours that it took for him to transcribe his answers to these questions – many of which were suggested to me by his fans and fans of the George Reeves community. Though this interview took place via email and Facebook, I hope to meet Jim in person one day or at least speak with him on the phone.

Jim Beaver’s philosophy is summed up in this quote by Thomas Wolfe:

"Man is born to live, to suffer, and to die, and what befalls him is a tragic lot. There is no denying this in the final end. But we must deny it all along the way."

References

Life's That Way – by Jim Beaver

Photos, and quote, courtesy of Jim Beaver’s Facebook account

Editor’s Note (Richard Potter): I want to thank Susan Schnitzer for providing this outstanding interview with Jim Beaver. I also want to thank Jim for his patience and candor in answering Sue’s questions. Several years ago, the TV program Unsolved Mysteries hosted a segment on the mysterious death of George Reeves. Jim Beaver was one of the experts consulted for the show along with Jim Nolt and Michael Hayde.